View West From Schoodic Point Across Frenchman Bay Towards Cadillac Mountain on MDI, E. Mark Photo, March 27, 2015

Adaptive Shelter Healing Landscape

ALAR 8020 ARCH 4020 Design Studio __ Spring 2025

Instructor: Earl Mark, PhD, Associate Professor of Architecture

Note: This web site is currently under construction with new content being added. It's viewable but not fully implemented for small smart phone screens.

A SANCTUARY FOR FORCIBLY DISPLACED PEOPLE

This studio focuses on the needs of forcibly displaced people relocated to a rocky peninsula extending into the Gulf of Maine. The location is in Downeast Maine within a separated northeastly part of Acadia National Park. The residents' involvement in the building of their shelters and caring for this national park's coastal setting creates a two-way healing process. Their stewardship of the coastal and marine ecology is integral to their own recovery from the trauma of forcible displacement.

Adrian Parr Zaretsky, Dean and Landscape Architect at the University of Oregon, describes transpecies design as "a non-anthropocentric approach to regenerating, restoring, reinvigorating and replenishing the natural environment." [1] Thus, rather than focusing solely on human forcible displacement experience, her design principles would emphasize the interconnectedness of animals and plants as both the starting point and goal. In keeping with this approach, students may elect to explore how the two-way healing process can address the migration and survival of non-human species facing dislocation or extinction.

INTRODUCTION

When people are forcibly displaced, traumatized, separated from their loved ones and support networks, and in urgent need of food, medical care, sanitation, and shelter, time is critical. A rapid response can save lives. Providing flexible, quickly deployed shelters within a secure perimeter is often a vital first step for survival. Within the larger setting, site designs that therapeutically engage with the natural environment can help people heal from physical and psychological trauma. However, refugee settlements, initially created under urgent conditions, often expand and endure far longer than expected. The original layout may quickly become inadequate for supporting the health, self-determination, religious and cultural practices, and sense of hope of residents.

We will examine best practices in Shelter and Settlement case study literature and documentation. However, each studio participant is encouraged to research their own selection of a forcibly displaced people, develop their own thesis or interpretation of the context for this exercise, advance their own propositions about the appropirate response, and speculate about innovative approaches to address what has become an increasingly urgent and escalating global issue. As of the end of 2023, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there were 117.3 million forcibly displaced people in the world, greater than at any point recorded in history. The practice of architecture will need to adjust to the resource constraints, calculated risks, and uncertainties that this cirumstance creates.

The current approach to temporary settlements has a mixed record of success. Religious, cultural, political, and social conflicts may be difficult to resolve within a rapidly deployed settlement. Limited and uncertain resources are common challenges. Climate change, infectious diseases, and spatial constraints further complicate these efforts. Pre-designed shelters may be ineffective if not developed in close collaboration with the displaced community and without granting them agency. That is, their modification and innovation of their living environment may be needed to reframe the requirements so as to better match their hopes, active engagement, and the specific trauma of their forcible displacement.

Therefore the studio will explore how to prepare for the evolution of settlements for displaced communities, focusing on the initial setup not as a permanent solution, but as a flexible framework for later customization and eventual long term changes that may be needed over time. Students will design adaptive, lightweight rigid and tension membrane fabric collapsible structures that can be rapidly staged and customized over time to meet the evolving needs of at-risk communities, their cultures, and their living patterns. Each student will also explore the healing potential of natural and built environments by designing a site for a specific group of displaced people with a small environmental footprint that is compatible with plant and animal habitats, and, especially in this area, nesting sea birds.[2]

The hypothetical project site is based in Maine’s Downeast Coast at Acadia National Park’s Schoodic Peninsula where we will stay for several days, tentatively scheduled for March. This trip will also include meetings with fabricators specializing in tension membrane fabric systems, as well as sailmakers and wooden boat builders from Maine, given their expertise and innovation with lightweight structures. Travel to Maine and the studio program is funded through a foundation grant.

STUDIO PROGRAM FOR A UNHCR DEFINED COMMUNITY

Figure 1: Za'atari refugee camp, a few months after the initial settlement, entering a adjustment phase in anticipation of winter. Photo _ Panorama: Za'atari Refugee Camp, Jordan 21 November, 2012. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by BY-NC-ND 2.

The studio program starts with the design of a single household unit. By midterm, the scope expands to a cluster of 16 units, accommodating 80 residents—a population size recognized by the UNHCR as a "community." In addition to housing, common-use structures will be integrated. Students are encouraged to incorporate a second "community" while keeping building size limits, allowing for detailed investigation of connection joints, materials, structural principles, land use, environmental footprint, and overall climate and site conditions.

For settlements that outlast their original emergency purpose, we will explore how structures can retract and expand daily, adapting their spatial organization to meet evolving needs over a longer transitional period. Additionally, we will examine how to support the healing of forcibly displaced people, fostering responsible stewardship of the natural environment in ways sensitive to their trauma.[3] [4]

SITE

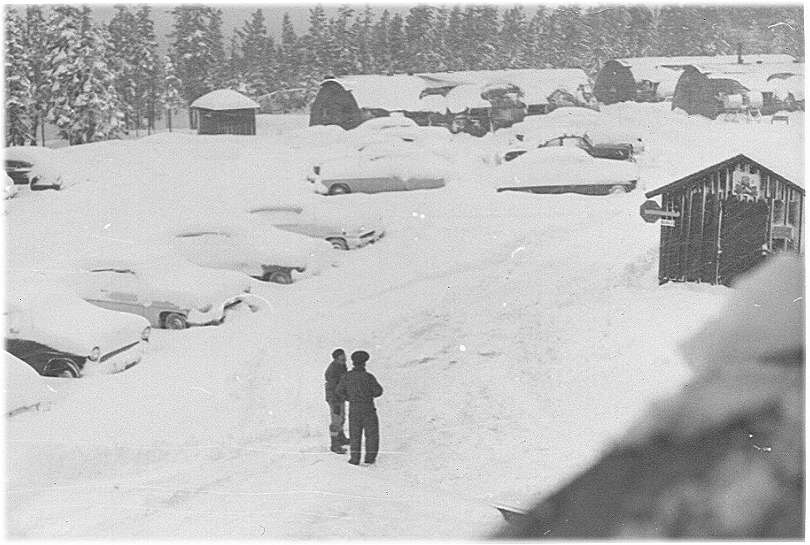

Studio participants will choose a site on the grounds of a former U.S. Naval Radio Station(R), adjacent to Schoodic Point. A temporary housing type, Quonset Huts, were added to the Naval Radio Station to keep up with its expansion as shown in figure 1.

Figure 2: 1957 Photo of US Naval Radio Station, Schoodic Peninsula, Collection of Tony Spatafore, NSGA, Winter Harbor Maine.

The peninsula points outward into the Gulf of Maine. Frenchman Bay to the south and west lies between it and Mount Desert Island, the more frequently visited part of Acadia National Park. It's land area is highly vulnerable to natural disturbances such as a Nor'easter, Significant Snow Storm or Blizzard. On the one hand this setting is prized for its natural beauty, pink granite shorline and sweeping ocean views. On the other hand, it faces a number of environmental challenges that can render it vulnerable to loss of infrastructure, marine habitats and to erosion. A Winter storm in January 2024 caused significant damage to the loop road around the peninsula as shown in figure 3.

Figure 3: January 2024 January Photo of Winter Storm, NPS.

We will examine these environmental risks that may be similar to conditions that impact refugee settlements elsewhere, especially due to climate change and sea rise . We will consider where national park preservation goals may conflict with permitting naturally occuring dynamic ecological changes. Relevant to the trauma experienced by forcibly displaced people, we will explore through site design and programing the potential of this ocreanfront landscape to serve as a healing agent if designed to more consciously encourage it's inhabitants to better know, safeguard and actively care for it.

SIGNIFICANCE

Given the escalation of global conflicts, climate change and natural disasters, the number for forcibly displaced people seems likely to increase. The annual rise in displacement has consistently surpassed historical levels. When this studio was first offered in the spring of 2016, the UNHCR reported 65.6 million forcibly displaced people (UNHCR, 2016 in Review). In just a few years, that number has nearly doubled, exceeding the population of 218 out of 234 countries worldwide—roughly 93% of all nations. Today, the number of forcibly displaced people surpasses the population of every U.S. state and nearly every European country (with Russia being an exception).

Such figures overwhelm the capacity of the UNHCR and other humanitarian organizations to keep pace. Displacement circumstances vary widely, and resources are often scarce. In an ideal world there would be abundant building materials, skilled design professionals, and construction personnel, allowing for thoughtful and deliberate project execution. However, the current pace of displacement forces designers to work quickly and improvisationally, with limited resources, information, labor, and materials.

Despite these challenges, it is widely accepted in humanitarian aid organizations—including the UNHCR, IOM, and USAID—that involving displaced communities in the planning of their own living spaces can aid recovery from the traumas of displacement. Additionally, access to green spaces and nature can have significant positive effects on physical and mental health, given the right conditions.

Initially, shelter provisions may begin with limited solutions constrained by urgent timeframes, supply chain disruptions, and uncertain land tenure. Early-stage shelters are often lightweight, tent-like structures assembled using simple tension cable rigging. Over time, displaced residents may modify and expand these shelters, reflecting healthy community engagement and agency. Examples of this can be seen in the Zaatari Refugee Camp in Jordan and the early phases of the Kara Tepe refugee camp on Lesvos Island, Greece, where the IRC, UNHCR, and local partners provided a supportive and adaptable environment. This allowed residents to set up shelters, create social and cultural venues, and develop a site with good drainage and views of the Aegean Sea.

However, overcrowding and social tensions eventually destabilized Kara Tepe, leading to unsafe conditions. This forced the camp to close, and refugees were relocated to more secure facilities. These security-focused shelters, with restricted access, have faced significant criticism from the humanitarian aid community. The negative impacts on refugee mental health have been widely reported in the press and documented in case studies by various aid organizations.

SELECTING A NARRATIVE

Readings and topics within the studio include profiles of forcibly displaced peoples, their varied circumstances, cultures, and particular needs as described by humanitarian aid organizations and health care providers. Each design studio participant will independently select, research and respond to the discrete narrative of a particular group of forcibly displaced people. For case studies in the field, see also the bibliography, a working document on this web site that will be continually updated. You are invited to explore a design interpretation that reflects your own perspective on the requirements of forcibily displaced people and to shape the program to an interpretation that resonantes with your thinking.

TRAVEL TO THE MAINE COAST

A field trip to the Maine Coast willl tentatively overlap with the first weekend of Spring break. Airline, lodging and transportation costs, and several dinners in Maine will be covered. The trip includes a walking tour of the ecosystem, habitats, plants and animals and oceanfront setting with emphasis on the environmental footprint of existing and potential built structures. It will be led by State Park Ranger and/or Environmental Scientist. See Field Trip menu item for more details.

UNHCR RAPID SETTLEMENT STANDARDS

The UNHCR settlement layout standards are based on the base group of a “Community” site plan consisting of 16 household units. Sixteen “Communities” are in turn aggregated into a single “Block”. Four “Blocks” are aggregated into a “Sector”. Finally, four “Sectors” are in turn aggregated into a “Settlement” for roughly 20,000 people. While the studio will be focused on the “Community” scale, it will more abstractly consider implications at the “Settlement” scale.

NOTE ON DESIGN PROCESS

On the one hand, the studio will focus on a tangible approach to working with materials, physical modeling making, tension structural experiments, while minimizing an ecological footprint. As reinforced by the field trip, harnessing the healing powers of a landscape context offers more options for interpretation within the constraints generally imposed on building within National Parks.

On the other hand, as the design profession is learning to adapt to new paradigms of professional practice, we will explore what it means today to be a design professional in an increasingly underresourced and conflict ridden world, where understanding context, methods of contruction avaible, social and environmental conditions require at times a more nuanced application of a designer's responsibilties, where the choice of materials and empowerment in construction of the community being served is important to the success of the outcome.

INSTRUCTOR BACKGROUND / QUESTIONS

Earl Mark has been teaching collapsible tension membrane fabric architecture studios at the University of Virginia since 2007, focusing on sites along the Maine Coast, primarily at Schoodic Point in Acadia National Park. During a research sabbatical in 2015, he tested small-scale mockups of tension membrane fabric housing equipped with sensors to automatically retract and unfurl solar shading. This research evolved into an adaptive shelter program for forcibly displaced people in 2016. He has taught similarly themed vertical studios at the University of Oregon (2019, 2022, 2023) and seminars at UVA since 2018. The contributions of Professor Emeritus Reuben Rainey, particularly his research on healing gardens have been influential. Rainey's work on landscape architect Garret Eckbo’s designs for Depression-era camps in California, built by the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s, has been significant to the site planning concepts explored in the studio.

Mark is currently collaborating with the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and partner organizations to address educational and research priorities in design education focused on the needs of forcibly displaced people. His current research examines the daily movements of displaced individuals in Greece in partnership with colleagues in Athens. He is developing plans for shelter and settlement research with partners in biomedical engineering and WASH systems in Bangladesh.

Questions about this studio are invited. Individual appointments may be arranged by sending email to Earl Mark at ejmark@virginia.edu.

END NOTES

[1]. Parr Zaretsky, A., & Zaretsky, M. (Eds.). (2024). Transpecies Design: Design for a Posthumanist World (1st ed.). This publication is availble as an e-book in the UVA Library: Routledge. https://doi-org.proxy1.library.virginia.edu/10.4324/9781003403494

[2]. The studio will reference Prof John Anderson's teaching and reserach at the College of the Atlantic on Sea Birds, Ecology, and Animal Behavior. Anderson maintains that natural habitats adapt to changing environmental conditions. Inflexible preservation practices can be a threat to their survival.

[3]. We will examine the implicatios of the

recently published research in Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Wellbeing by Jenny Roe and Layla McCay that gives evidence of the neurological and mental health benefits.

[4]. Reuben Rainey, Emeritus Professor of Landscape Architecture, asserts that “There is no such thing as a generic healing garden”. Panel Discussion, UVA, 2013. It is to be designed for a specific group’s needs.

Copyright © 2025 . Earl Mark . ejmark@virginia.edu. University of Virginia. All rights reserved.